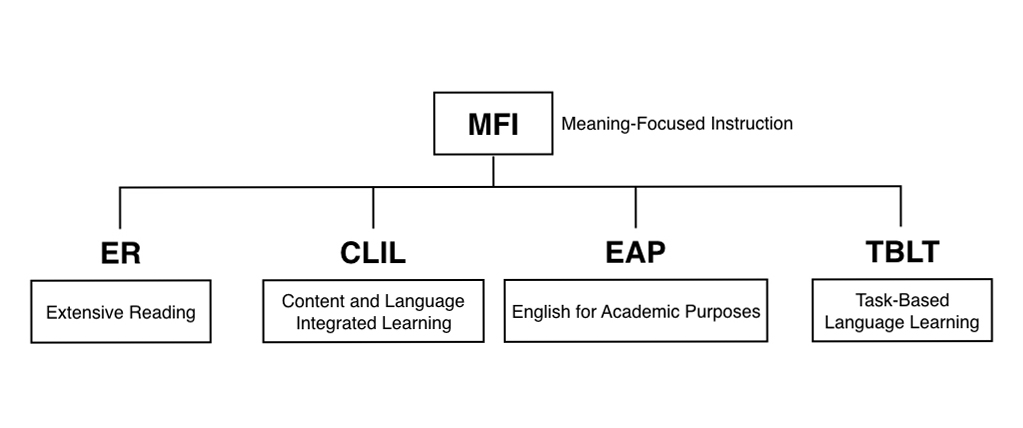

Meaning-Focused Instruction (MFI) takes an indirect approach to L2 instruction. It is often contrasted with Form-Focused Instruction (FFI), a direct method of language instruction. With MFI, students learn language incidentally when they attend to meaning. That is, when students focus on texts for the sole purpose of understanding meaning, they also pick up an understanding of both grammar and vocabulary. Language acquisition is thus a by-product of this focus on meaning. It is based on the idea that we learn when we notice how meaning is expressed by form, and how form expresses meaning, a premise well supported by research. Furthermore, this theory underpins many of the common pedagogies in our field, including: ER (Extensive Reading), CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning), EAP (English for Academic Purposes), TBLT (Task-Based Language Teaching) and others. As a pedagogy, MFI got its start in the 1960s in the language immersion programs in Canada, where students learned either English or French by taking classes in other subjects where the language of instruction was the foreign language.

A key psychological concept in MFI is salience. In psychology, “the term salient refers to anything (person, behavior, trait, etc.) that is prominent, conspicuous, or otherwise noticeable compared with its surroundings”. In language teaching, salience refers to language input that somehow “stands out.” And research tells us that language input that is more salient is more likely to be deeply processed and subsequently acquired. Furthermore, given that learners generally engage with the meaning of language before attending to its form, meaning-focused instruction is more likely to lead to language being salient, noticed and acquired.

Although the effectiveness of MFI is well established in the research literature, research has also shown that MFI alone can be insufficient. For example, studies into Canada’s immersion programs found that students did NOT always attain high levels of grammatical proficiency or sociocultural appropriacy. This suggests that while incidental learning is useful for language development, there are limits. Researchers have found that students who use English to communicate or understand some kind of meaning can fail to pay attention to grammatical features that are not key to the meaning they are communicating. This suggests that while MFI is important, some focus-on-form, or form-focused instruction, is also beneficial. And FFI can have as its focus any aspect of language, including: grammar, vocabulary, phonology, or sociocultural appropriacy.

There are obviously many ways for teachers to direct student attention to form. For example, teachers could directly explain something to the students. Another way might be to set some kind of task that allows the students to discover for themselves the language point you are trying to teach. The key point being, we as teachers, from time to time, need to direct student attention to the structure of language.

An important theoretical underpinning of all this is the Noticing Hypothesis. According to well-known linguist Richard Schmidt, “input does not become intake for language learning unless it is noticed, that is, consciously registered.” This suggests that while our classes need to focus on meaning, at the same time, teachers also need to point out, through form-focused instruction, those features of language that might NOT be salient and therefore less likely to be incidentally acquired. That is, our classes need to strike a balance between MFI and FFI.

Next, it is well understood that students need to get extensive L2 input if they are to be successful. Typically in Japan, students do not get nearly enough L2 input. That is, the time spent in class is insufficient. To be successful, students need to engage with the language OUTSIDE of class. However, to do this, students need to have enough skill to make any engagement with English outside the classroom enjoyable. And it is usually this, a lack of skill, that thwarts student engagement outside the classroom.

Lastly, students need an opportunity to output their L2. Without output, students are unlikely to become fluent. To become fluent, language must be automatic and routine, which usually requires a great deal of task repetition. In addition, output also helps to develop language accuracy, as students are forced to focus their attention on how form expresses meaning when they speak or write.

In short, our classrooms should be vehicles not only to help students use English meaningfully, but also develop their skills through FFI. And if they can develop enough skill to enjoy English, they will begin engage with English voluntarily outside the class.

Comments(0)

Leave a message here